On this page, you can find lots of resources which summarise Cochrane evidence on breastfeeding and aim to make it easy to access. The content is based on this Cochrane Special Collection of systematic reviews on breastfeeding, as well as later Cochrane Reviews. You can either scroll through this page, or click on the topics below to jump straight to a particular section. This page is part of a series of blogs called ‘Maternity Matters’.

Page last updated: 21 June 2023

- Support for breastfeeding women

- Health promotion and an enabling environment

- Care for breastfeeding women and their babies

- Treating breastfeeding problems

- Breastfeeding babies with additional needs, including preterm babies

- Related clinical guidelines and resources

__________________________________________________________________

Support for breastfeeding women

“Providing women with extra organised support helps them breastfeed their babies for longer. Breastfeeding support may be more helpful if it has 4‐8 scheduled visits. There does not appear to be a difference in who provides the support (professional or non‐professional) or how it is provided (face‐to‐face, phone, digital technologies or combinations).”

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

[sta_anchor id=”health-promotion” unsan=”health promotion”].[/sta_anchor]

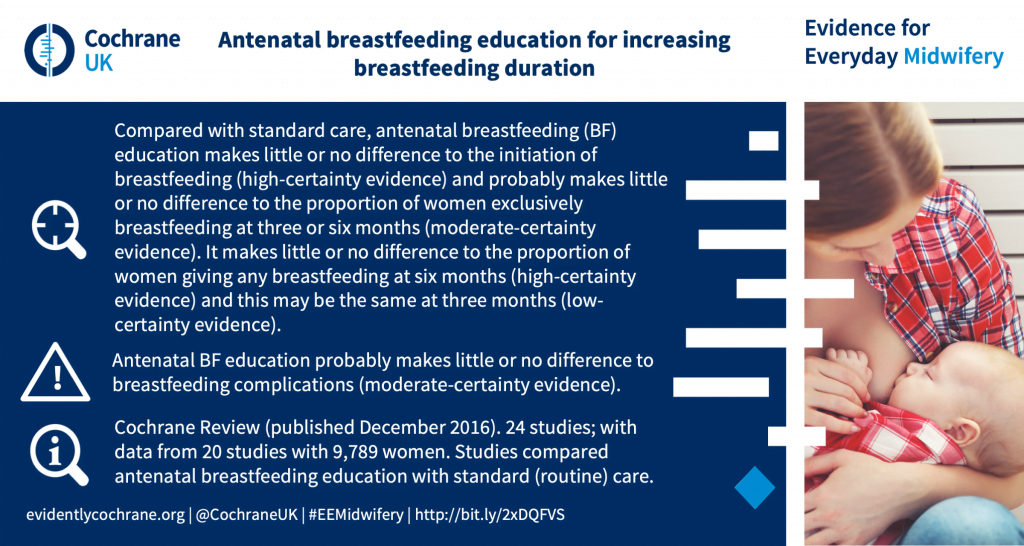

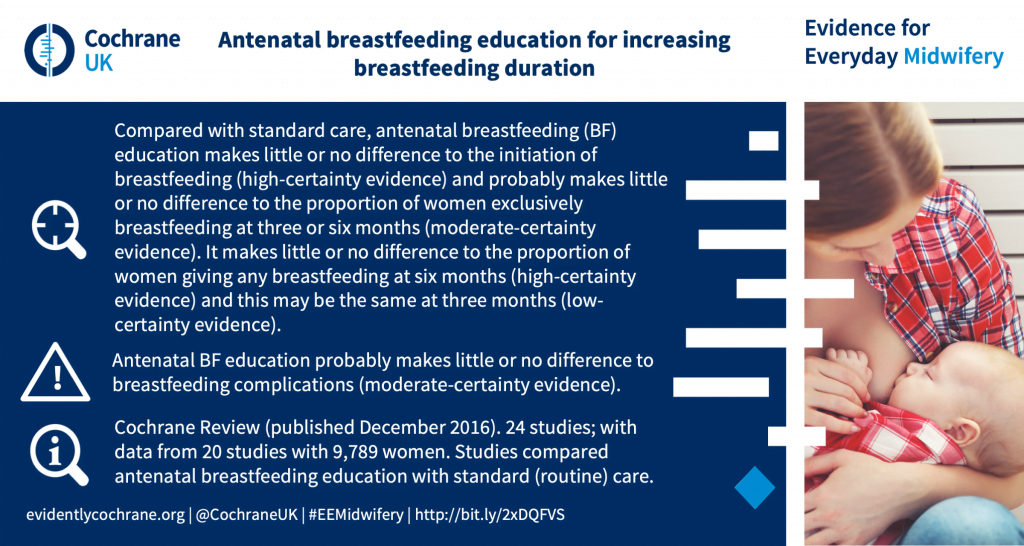

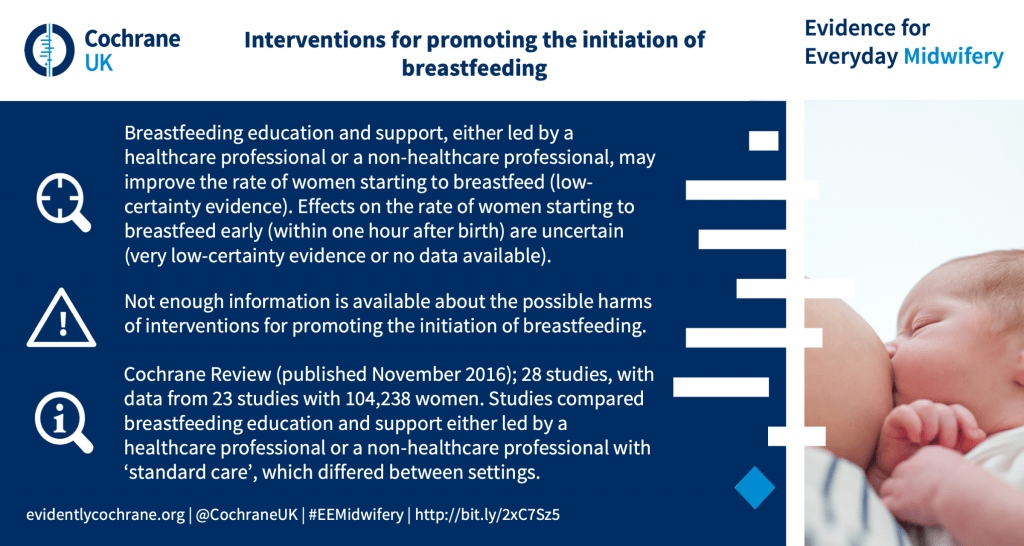

Health promotion and an enabling environment

Health promotion and enabling environment

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Care for breastfeeding women and their babies

Care for breastfeeding women and their babies

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

[sta_anchor id=”problematic-breastfeeding”]Problematic breastfeeding[/sta_anchor]

Treatment of breastfeeding problems

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

]

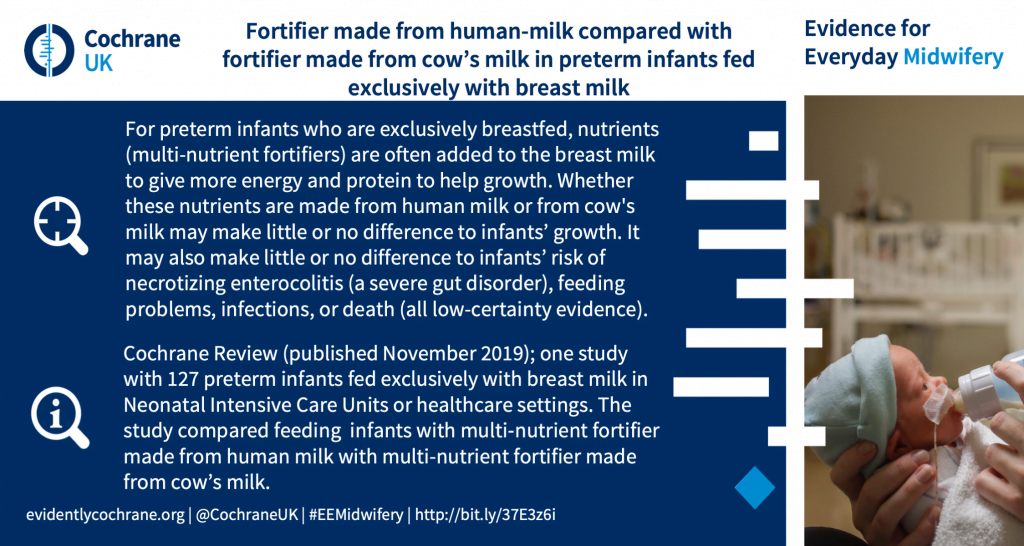

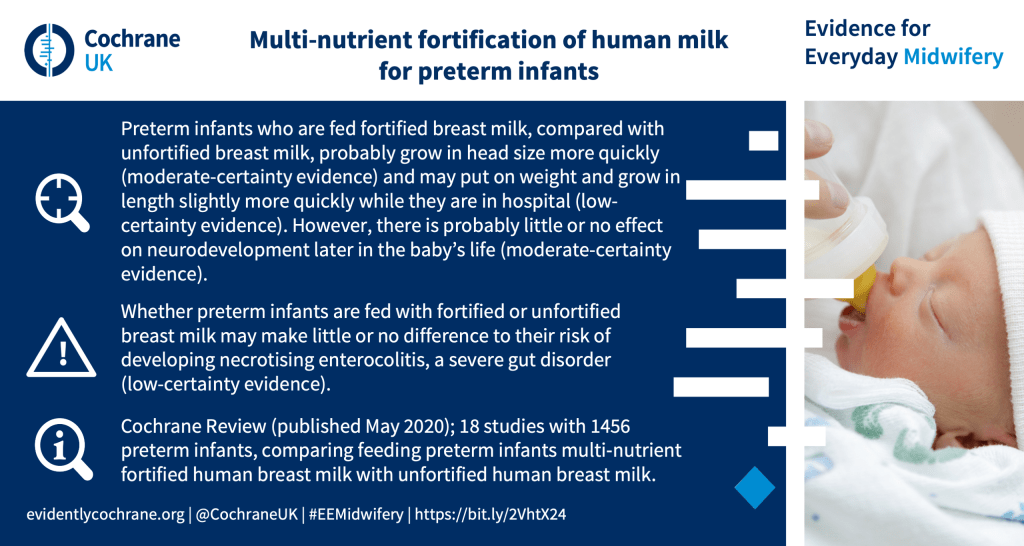

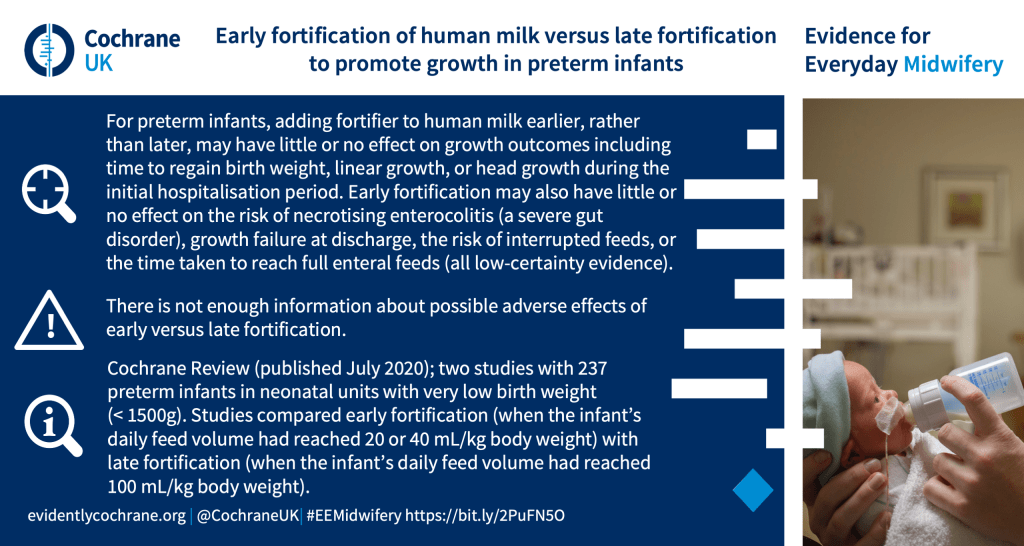

[sta_anchor id=”feeding_practices”]Feeding practices for preterm babies, or babies with additional needs, and their mothers[/sta_anchor]

Feeding practices for preterm babies, or babies with additional needs

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

[sta_anhor id=”related_breastfeeding_reading”]Related clinical practice guidnce and guidelines informed by Cochrane evidence[/sta_anchor]

Related clinical practice guidance and guidelines informed by Cochrane evidence

- Bacterial infections specific to pregnancy: clinical practice guideline (Royal College of Physicians of Ireland; 2018).

- Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Breastfeeding problems.

- Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Mastitis and breast abscess.

- WHO Guidelines: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services.

See also:

- New baby: fads, fashions and evidence for new parents. In this blog for people expecting or caring for a new baby, Sarah Chapman looks at some common concerns and tackles fads, fashions and hard evidence.

[…] rates are still low. The Cochrane Library, which carries out large reviews of the evidence, notes that antenatal classes teaching women about breastfeeding have no detectable effect on uptake, and […]