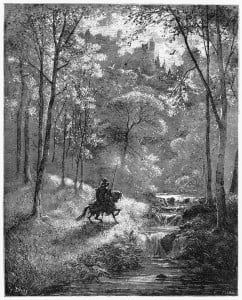

In this blog, retired GP Richard Lehman writes of of the dearth of evidence on treatments for delusional disorder and hopes there may be an abundance of kindness, as illustrated by Cervantes in his tale of Don Quixote.

Page last checked 24 August 2022

The Oxford Lunatic Asylum opened in 1826, set in ten acres of fields and woods on Headington Hill among which the inmates could wander and look at the dreaming spires below. It was later renamed the Warneford Hospital, after a vicar who gave it generous endowments. When I was a medical student on a psychiatric attachment there over 40 years ago, it still had a slightly informal, family feel about it. “We get more Firsts than any other college in Oxford” was one of its boasts. A notable recent inmate had been a genteel, immaculately dressed college don who wrote a 40-page letter of appeal to the governors, signed “Edward IX, R.” The governors decided to keep King Edward IX in their relaxed confinement.

When I read the Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. of Treatments for Delusional Disorder (published May 2015) last year, I remembered the King, and also Don Quixote, the most famous literary example of delusional disorder. In Cervantes’ books, the self-proclaimed Knight of the Sad Countenance is an unmarried eccentric of middle age in a small Spanish town. He has read so many books about deeds of chivalry that he becomes convinced that he is in a knight errant, bound to the service of his imaginary girlfriend Dulcinea. In the first book, he performs the mad deeds for which he is best known, such as attacking a windmill and slaughtering a flock of sheep in the belief that they are an army of the enemy.

The second book finds Quixote as deluded as ever, but Cervantes portrays him as now famous for his deeds in Book 1, meaning that he is often recognized on his quests. A kind Duke and his fondly mischievous wife give him lavish hospitality and contrive situations to bring out his valour for their amusement, but to their surprise find that he is also a wise, learned and loveable man. They begin to wonder if it is right to tease him and set him up. A priest and a scholar debate the point, and decide that he is indeed mad, but in one delusion only, and that there is no point in sending him to a doctor because there is no cure for such madness. It is better to just to keep humouring him and show kindness. And so the fun goes on, until Quixote grows ill and dies peacefully, half-cured of his folly at the end.

Despite writing what is perhaps the best-loved novel in history, Cervantes died a pauper a few years later and his remains were discovered only last March, not long before the Cochrane Review was published. Why have I left so little space to discuss this review on a fascinating subject? Unfortunately because it is nearly empty. The reviewers identified just one trialClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. on the treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. of delusional disorder which met Cochrane inclusion criteria, and their conclusion states that “There is currently insufficient evidence to make evidence-based recommendations for treatments of any type for people with delusional disorder… Until such evidence is found, the treatment of delusional disorders will most likely include those that are considered effective for other psychotic disorders and mental health problems.” In among the high jinks and ridicule of Cervantes’ deluded Don Quixote, we also see the role of kindness and social acceptance in early seventeenth century Spain. I hope these can still be found in early twenty-first century Britain, because this review doesn’t give me confidence that we have any better science to help the Don Quixotes and King Edwards of our time.

Links:

Skelton M, Khokhar WA, Thacker SP. Treatments for delusional disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. 2015, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD009785. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009785.pub2

Cervantes Saavedra M de (author). Shelton T (translator). The history of the valorous and witty knight-errant, Don-Quixote of the Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes. Translated by Thomas Shelton. London: Edward Blount; 1612 (Part One); 1620 (Part Two).

Cervantes Saavedra M de. El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha. Madrid: Francisco de Robles; 1605 (Parte Primera); 1615 (Parte Dos). (Original in Spanish)

What an amazing and thought provoking article. It’s so great to see that nearly empty Cochrane reviews can provide so much food for thought and inspire such informative, imaginative and inspiring writing.