Robert Walton, a Cochrane UK Senior Fellow in General Practice, blogs about the evidence on reducing saturated fat in our diets to help prevent cardiovascular disease.

Page last checked 28 June 2023

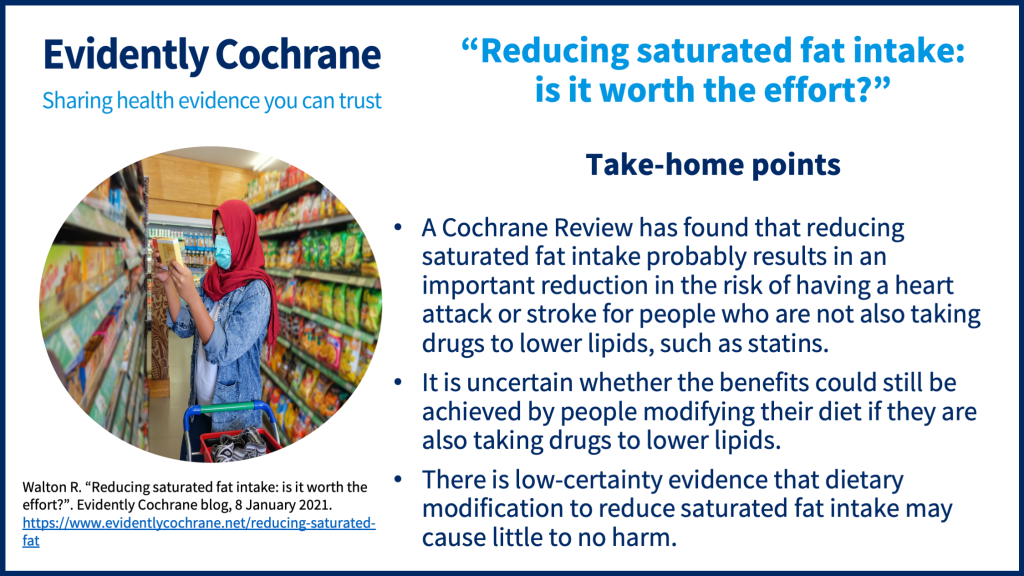

Few questions have caused so much controversy in science and medicine and debate over the breakfast table as the prevention of cardiovascular disease. A recent Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research., Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease (August 2020) gives an excellent summary of the scientific evidence thus far.

But what does it mean to you? Should you change your diet? And if you did what benefits would you gain? What harm might you come to?

So what’s the evidence?

Perhaps the most important evidence in the review comes from 15 randomisedRandomization is the process of randomly dividing into groups the people taking part in a trial. One group (the intervention group) will be given the intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) and compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the control group). controlled trialsA trial in which a group (the ‘intervention group’) is given a intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) is compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the ‘control group’). with 56,675 people taking part. Participants were asked to reduce the amount of saturated fat in their diets and were then followed over several years to see what illnesses they developed. When all cardiovascular events (such as heart attacks and strokes) were grouped together, there was probably a 17% reduction in events over the time course of the different studies. Overall people in the studies had a fairly high rateThe speed or frequency of occurrence of an event, usually expressed with respect to time. For instance, a mortality rate might be the number of deaths per year, per 100,000 people. of cardiovascular events with 8% having a heart attack or stroke over the time for which they were followed up.

However, although cardiovascular events themselves were less frequent with dietary modification there was no evidence of a reduction in deaths from all causes. This is an interesting finding and difficult to explain. One reason could be that it takes longer for the benefits of a low saturated fat diet to become obvious on deaths from cardiovascular disease than for the cardiovascular events themselves. That is to say people in the trialsClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. may have had a heart attack or stroke but not died as a result. Another explanation might be that reducing saturated fat in the diet reduces the riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of cardiovascular events and at the same time increases risk of death from other illnesses, however the authors of the review say that they found no evidence of this in the studies that they included.

Unfortunately the evidence was of low or very low-certaintyThe certainty (or quality) of evidence is the extent to which we can be confident that what the research tells us about a particular treatment effect is likely to be accurate. Concerns about factors such as bias can reduce the certainty of the evidence. Evidence may be of high certainty; moderate certainty; low certainty or very-low certainty. Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of evidence. Find out more here: https://training.cochrane.org/grade-approach for individual cardiovascular outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. such as coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction and stroke so it wasn’t really possible to distinguish the differences between the effects of diet on specific cardiovascular diseases. Interestingly there was no evidence of increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease itself which might tend to reinforce the idea that longer duration of studies would be needed to assess the effects on mortalitydeath. In the past there has been some concern about potential harms of reducing saturated fat intake but the review found no evidence of this although the evidence that was included in the review was of low certainty.

But how relevant is all this evidence now?

The sea change in prevention and treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. of cardiovascular disease came with the introduction of statins in the 1990s. Statins were more effective than previously available lipid-lowering drugs and although new lipid-lowering medications are available now statins are still the mainstay for cardiovascular prevention. Statins cause very marked reductions in cholesterol levels and also reduce the risk of death from all causes although at the risk of side effects such as muscle pain in some people.

The authors of the review attempted to assess the effects of increasing use of statins in later years by grouping the included studies into decades and examining the effects over time. The idea being that the effect of diet would be reduced as statin use became more frequent in more recent studies. There was no clear trend in this analysis although this may have been because there were relatively few studies in the statin era. Nevertheless three large trials in the 2000s showed no clear reduction in combined cardiovascular events from dietary modification. Thus one possible explanation may be that people taking part in these trials were protected from cardiovascular disease by using statins which masked the effect of the change in diet.

In 2014 there was a further change in strategy for prevention of cardiovascular disease. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), acknowledging the health benefits of statins, recommended that they should be used by everyone with a 10% chance of having a cardiovascular event over the next ten years. In practical terms this means statins should be offered to almost all of the populationThe group of people being studied. Populations may be defined by any characteristics e.g. where they live, age group, certain diseases. in England over the age of 60. So an important question now is whether dietary modification to reduce saturated fat in people taking statins will prevent illness and premature death.

We assume that the reduction in risk of death from using statins results from reduction in cholesterol. Thus given the substantial cholesterol reduction seen with these drugs, any additional fall from dietary modification might be small and therefore the health benefit accruing could be relatively minor. Unfortunately, most of the evidence presented in the review comes from old studies before statins were widely available and so does not shed light on this most important issue.

Perhaps then the evidence presented may be most useful for people who decide that they do not want to take drugs to reduce their risk of death from cardiovascular disease. In this event the review becomes highly relevant – modifying your diet to reduce saturated fat intake probably results in a worthwhile reduction in risk of heart attack and stroke.

So now you’ve had a chance to look at the evidence and read my musings shall I ask you the question ‘what would you prefer on your toast – butter or marg?’.

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @rtwalton123 @CochraneUK or leave a comment on the blog. Please note, we cannot give medical advice and we will not publish comments that link to commercial sites or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion. However we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish comments we consider offensive.

References:

Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. 2020, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD011737. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. Accessed 09 December 2020.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2016. (NICE CG181). [Issued July 2014; last updated September 2016; last reviewed January 2018; update planned]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

If we understand that the Hegsted equation is widely accepted. Would it not be more appropriate to indicate that saturated fats should be those that make Hegsted’s equation a value of 0? All this from the moment that if we adjust for cholesterol the risk “disappears”.

I would be very grateful to hear your views.

Thank you very much in advance